Clan MacColin

Military Guide

The MacColin military forces are made up of three parts: Pike, Kern and Galloglaigh.

The Pike is the primary weapon of every able-bodied male of military age (defined as anyone between "Pike-mitzvah" to "The Raleigh Hills Home for Old Celts"). This is regardless of your usual marching role or area of expertise. Our numbers are too small and, our jobs too varied, to afford any form of restricting specialization.

Pike requires nothing more than attendance, the basic costume, and a pair of heavy gloves, which are required gear for men. Welding gauntlets are very suitable for the last requirement. Pikes and polearms are Clan provided. See the forge crew, AND ME, if you wish your own.

The Kern are the skirmishers or light infantry. This requires more equipment than Pike and you are expected to provide your kit. The Kern needs the basic equipment for Pike plus a targe, a personal weapon (an axe or short sword), a missile weapon (throwing darts, staff sling, or bow), and some accuracy with the missile weapon. Armour is not necessary but arming coats are encouraged.

The Kern's traditional role has been rear guard but this will be changing over the next few months.

The Galloglaigh is our heavy infantry. Because of the cost of the equipment required this is our smallest force. The Galloglaigh need the basic Pike and Kern kit. To this is added an arming coat, chain or plate armour, a helmet, a weapon (polearm, Galloglaigh axe, or two-handed sword), and the ability to use these weapons.

This is only a brief description and explanation of the types of forces we have and their required equipment. Details and tactics can be researched in the Clan Costume Guide and from the handouts available.

Please check with me before you purchase this equipment. It is always unpleasant to tell someone that a just acquired, expensive item, is not suitable and cannot be approved. I just might have a cost-savings suggestion.

For as long as man has fought on foot there have been two major types of forces: the heavily armoured and equipped infantry, and the lightly armed skirmisher: the light infantryman. The Greeks of the Classical era called them Peltasts; to the Romans, they were velites; and to the Scots and Irish of the 16th century, they were the kern (cathairne) or cateran.

The name by which the light infantry were known may have changed over the centuries, but their arms and armour and tactical roles remained almost unchanged from the time of Xenophon and Belasarius to Fitzmaurice and the O'Neill. So the Irish or Scottish kern of 1570 was virtually the same as the kern that fought the Anglo-Normans under Strongbow in 1169.

The light infantry (or kern) is just that: a lightly-armoured force, armed with a variety of missile weapons. The kern combined speed and mobility with missile fire to defeat the enemy, instead of using the massive shock action of heavy infantry. The kern used these tactics to skirmish in advance of the main force, to harry the flanks of the enemy, ambush him, and act as scouts and foragers.

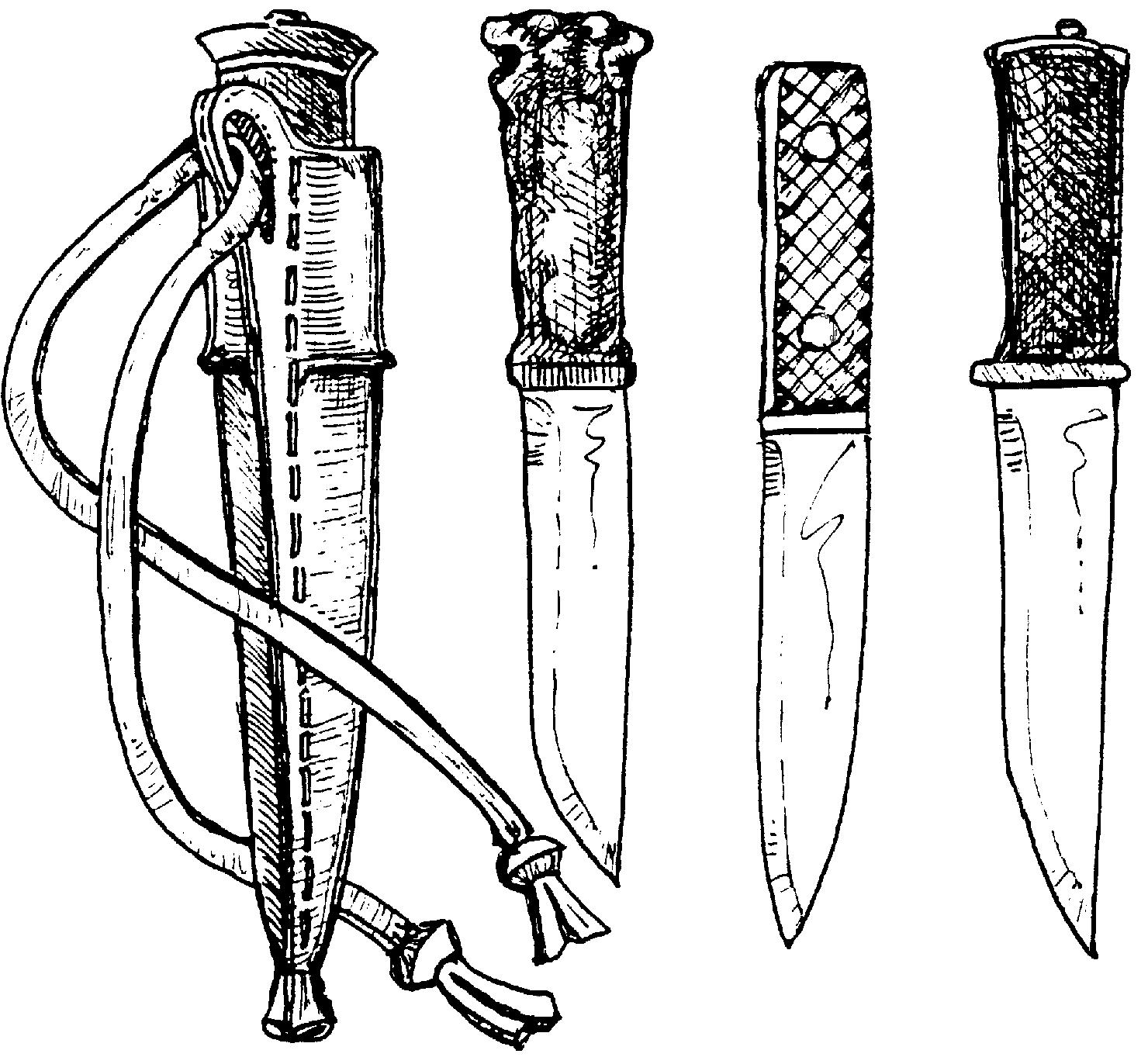

The individual arms and equipment varied with the wealth, experience, age, and battlefield acquisitions of the individual. In general, the kern was armed with a dirk and sometimes a sword or axe. His main weapon was a throwing dart: a kind of javelin three to five feet long, fletched at the end. The kern carried many of these and "cast with a wonderful facility and nearness, a weapon more noisome [annoying] to the enemy, especially horsemen, than it was deadly."

Besides the darts, short bows, crossbows, slings and staff slings, throwing axes and matchlocks were used. Slings and staff slings were carried by the younger or less well-equipped soldier. The crossbows and matchlocks were used by the older, better outfitted (more sucessful) professional soldier. But these other missile weapons were not used in anywhere near the numbers of the throwing dart.

The kern went into battle at best only lightly armoured, and often unarmoured altogether; armour only slowed him down, and in the bogs and forests, it was a liability. Poverty and long custom reinforced this attitude. If your father, your grandfather, or anyone in your family, village, or neighborhood did not fight in armour, there was a good chance you would not either. By the end of Elizabeth's Irish wars, however, this was changing. Armour and firearms for the kern grew much more common; but that is at least 30 years past our period. (Our grandchildren will be better armed than we are.)

The armour the soldiers of our time did wear was light and simple. If a helmet was worn, it was along the lines of a light steel skullcap, or a steel-reinforced leather cap. Plate armour was not worn; some chain mail was used but it was not very common. Both plate and mail were the province of the heavy infantry, the galloglaigh.

The kern sometimes carried shields known as bucklers and targes. The buckler was the smaller of the two, being about 12 to 16 inches in diameter and held by a handle, where the targe had an 18- to 24-inch width and was held on by straps across the forearm. Other protective equipment might include a padded garment like a gambesson or acketon. Again, a wealthy or experienced professional soldier might have a leather jack or brigandine, but this was the rare exception.

The best tactical use of the kern was in support of the galloglaigh, or in guerilla operations. These best used the kern's mobility and missile fire. Being lighter equipped, they could outrun the heavily armoured English soldier through the bogs and forest. Their missile weapons allowed them to inflict casualties at a distance safe from the "push of the pikes". The kern were well employed as skirmishers in front of and along the flanks of the galloglaigh. Their task was to disrupt the enemy formation with missile fire prior to the galloglaigh charge. If the charge broke the enemy formation, the kern on the flanks were in a position to pursue the fleeing enemy. As guerillas, the kern ambushed enemy formations, cut supply and communication lines, scouted the enemy and foraged the countryside for supplies. One of the best examples of this guerilla action was the fight against the forces of Sir Peter Carew by the Desmonds and Butlers in 1568.

Sir Peter Carew invaded Leinster with a force of English militia and Irish mercenaries. Carew quickly overran Leinster, sacked Kilkenny and captured most of the strongholds, and dispersed the Butler forces. Desmond and Butler fought back by scorching the earth in front of Carew, and by ambushing his columns and foraging parties. Short of supplies and facing increased opposition, Carew withdrew back to Munster. The Irish kern swarmed over the columns, cutting off small parties and picking off stragglers. Carew's forces were ambushed at every river crossing and ford, from behind every hedgerow and tree. The kern cut trees to form road blocks (called arbatis) at every forest track, and dug trenches across paths in the bogs. Carew's encampments were raided throughout the night. His forces virtually disintegrated and streamed back into Munster, only to find that Butler and Desmond had crossed over before him, and were busily pillaging Carew's own holdings and those of the English Munster colony. Without a single pitched battle, Carew was defeated: ambushed and skirmished to pieces.

An important tactic used by the kern was the relay ambush. The kern moved parallel to the enemy column, sniping at them with crossbow and matchlock fire. When the soldiers using the weapons were exhausted or out of supplies, they would pass the weapons on to other kerns farther along the line of march.

While the fight against Carew points up the kern's strong points, the battles for Kilmallock point out their weakness. Henry Sidney attacked the Irish forces under Fitzmaurice, the captain of the Desmonds at Kilmallock (the gateway to Desmond territory). After seven days of fighting, Fitzmaurice was beaten in a conventional fight in the open, by the English pike and by English firepower. Five months later, Fitzmaurice tried to retake the town. He beseiged the English garrison with 1500 kern and galloglaigh and 60 horse, and tried to starve them out. Humphrey Gilbert and 100 horsemen rode a sortie out of Kilmallock, broke the seige, and drove off the entire Irish force.

Some time later, Fitzmaurice did retake Kilmallock. With the help of folk in the town, 100-200 kern climbed the walls and entered the town in a dawn attack. The English garrison was taken and the town leveled.

The kern character is

ideal for the newcomer to Clan MacColin, since it requires very

little in the way of equipment or time (other than that spent

learning pike drill and other Clan activities!). All that is needed

is a leine, brat, a dirk and some sort of missile weapon. Throwing

axes are easy to come by and throwing darts are easy to build. It is

perfectly all right to remain with this unpretentious character,

also, as the kern were the most numerous of forces, and are always

needed. As experience and knowledge are gained, and as the wallet can

afford, equipment can be upgraded, if desired. A sword or axe can be

added, and targes and armour can be made or acquired.

{Galloglaigh; SEAN 30 6/25/84}

"Gall"

in Gaelic means foreigner, "oglaigh" means young fighting

man. The galloglaigh were the heavy infantry of the Western Scottish

Highlands and of Ireland.

"Gall"

in Gaelic means foreigner, "oglaigh" means young fighting

man. The galloglaigh were the heavy infantry of the Western Scottish

Highlands and of Ireland.

The galloglaigh produced among native Irish were called "buannadha." The term "galloglaigh" was usually reserved for Scottish mercenaries who were employed by Irish lords in every conflict from the first mention in the 13th century until the early 1600's. These mercenaries eventually became a permanent, hereditary military caste in Ireland. The galloglaigh families served many Irish lords for generations, became lease- and landholders to these lords, and intermarried with the local Irish. Clansmen of the MacDonalds of the Isles were hereditary soldiers to the O'Neills of Ulster; by the 17th century these MacDonalds were the 'O Donnalls of Ireland. Other galloglaigh families were the MacSweeneys and MacSheehys.

Another term for Scottish mercenaries in Ireland was "Redshank" or "New Scot." These terms referred to any Scottish mercenary, galloglaigh or kern. Redshanksand New Scots were usually seasonal in their service in Ireland. Most of the clans of the Western Isles and islands -- Campbells, MacLeans, MacLeods, MacKays -- sent Redshanks to Ireland.

The arms and armour of the galloglaigh changed little from the 13th century. The troops wore an akeaton, or a quilted jacket; over it a chain mail hauberk or byrnie. On their heads were skullcaps, or simple bascinets and kettle hats. Additional protection was provided by mail tippets and hoods. Very little plate was worn; it seems to have been a matter of preference, not availability.

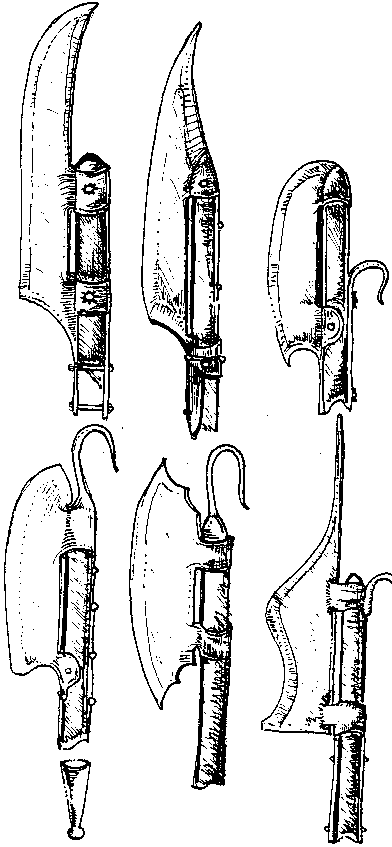

The galloglaigh carried a characteristic weapon: the sparth or axe. It is closer to a poleax than an ordinary axe. The English described it as "...a battle-axe, six foot long, the blade whereof is somewhat like a showmaker's knife; the stroke whereof is deadly where it lighteth." The sparth is a two-handed weapon, which means a shield could not have been used. Each galloglass carried a dirk, and often a sword.

Each galloglass was served by two kerne, who acted as gillies, foragers, and as an auxiliary force. Eighty galloglaigh, or 240 with kerne, were considered a battle or battalion.

The tactics of the

galloglaigh were very simple. They only had one: Charge into 'em!

They used it from the 13th century up to Tyrone's Rebellion. The way

it worked (or didn't) was to have the galloglaigh form up into a

block, or blocks, receive the last rites and blessings from the

priests, have a few drinks of the local brew, and work themselves up

into a fighting fury. The kerne went ahead and skirmished with the

opposition, and tried to soften them up with a little missile fire.

Then the big boys charged, with a salvo of high-pitched cries (Irish

soldiers in the British Army still holler the same way). They tried

to get among the enemy and cut them up with their sparths.

The tactics of the

galloglaigh were very simple. They only had one: Charge into 'em!

They used it from the 13th century up to Tyrone's Rebellion. The way

it worked (or didn't) was to have the galloglaigh form up into a

block, or blocks, receive the last rites and blessings from the

priests, have a few drinks of the local brew, and work themselves up

into a fighting fury. The kerne went ahead and skirmished with the

opposition, and tried to soften them up with a little missile fire.

Then the big boys charged, with a salvo of high-pitched cries (Irish

soldiers in the British Army still holler the same way). They tried

to get among the enemy and cut them up with their sparths.

The galloglaigh were most effective if they could close with the enemy, or if they attacked a force disrupted by missile fire, by terrain, or other distractions. For instance, a force might cross a stream and be broken into two groups, or might change from a marching column to a battle formation, and be attacked before they could complete the maneuver.

Unfortunately for the galloglaigh, the English forces in Ireland were pikemen, shot and horse. If the enemy was ready for them, and withstood the first mad rush, the galloglass usually got the worst of it.

The Battle of Monaster in the second Desmond War, on October 3, 1579, shows the characteristics of the galloglaigh.

The Irish had 2,000 men, kerne, galloglaigh and a little shot. The English, under Maltby, had 1,000 men, 600 of whom were trained in co-ordinated tactics (the Spanish square). The Irish formed up at daybreak. They took several hours to get ready and work themselves up to a charge. They charged the English formation, and Maltby's musketeers and calivers dropped many as they closed. The pikes kept the galloglaigh out of the English formation. The galloglaigh charged several times, and finally broke into the English formation; where they broke through they inflicted heavy casualties, but their breakthrough is repulsed. The Irish committed their last reserves, and Maltby countered with a cavalry charge by a small group of horse. The charge broke the Irish attack. The Irish retreated back into the woods and dispersed.

The Irish lost 500 of their 2,000; Maltby lost less than a quarter of his force.

If the charge didn't work, the response was to fall back, re-form and try again, although the second charge wouldn't be delivered with nearly the enthusiasm of the first. If the second charge failed, it was usually, "I think I hear my cattle calling..." and time to head home, hoping to hell the enemy didn't have any cavalry to chase you with.

The galloglaigh were effective against infantry of their own kind. They were vulnerable to English cavalry -- the axe was no pike -- but if they could get among them in a melee they could inflict considerable casualties. The galloglaigh weren't very good against pikes, unless they got an opening in the pike formation.

If the enemy was in a "Spanish Square" of arquebuses protected by pike, the galloglass was in deep trouble. The arquebuses shot him up as he charged, and destroyed most of his shock value. The pikes kept him from closing in, and the guns shot him up.

Better luck next time.

Every man in Clan MacColin from age twelve on up should have among his basic gear a round shield, or targe (pronounced tahrdj). You have seen many of our men carrying them, and you have probably seen pictures of them in books on the Highlands. They are useful for Clan purposes because, among other things, they do set us apart from other groups whose shield shapes and decorations differ significantly.

The targe consists of a circular wooden base, covered with leather and decorated with metal studs and bosses. Older targes were small, perhaps a foot in diameter, and did not shield much more than the hand and forearm; they were armed with a spike, and with a dagger held in the hand supporting them, were more offensive than defensive items. Our targes are larger -- generally 16" to 20" across -- and do not have the spike at the center.

Many of our men have made their targes out of 5/8" thick plywood rounds available from hardware and lumber stores. The advantage of this is, of course, that the shape is already circular. We do advise against using the chipboard (reprocessed sawdust and glue) "table tops" as targe bases, since they are extremely heavy and do not stand up well to nails, dampness, and general use.

If you are a good woodcrafter, you might want to make your own targe base out of a couple of layers of thinner wood. Of old, targes were made of two layers of oak boards, with the layers set perpendicular to each other. Or you may use pine, and lay the top boards at a 60-degree angle to the bottom layer. It is easier to shape the boards before layering them together.

Old targes were covered with bullhide. This is still about your best bet for good looks and long wear. (Thinner leathers tear too easily, and exotic grains just aren't in period. Suede can work, but can also look a little sissy. Use at least 6 oz. leather.) For staining and finishing your leather, choose a color in the serious brown range -- black may be romantic, and bright yellow dashing, but you probably won't get to use them in the pike line!

You will need two rounds of leather. one will be for the back, and may be rather thin, inexpensive "blacksmith splits" leather over 3 oz., and just covering the back. Glue this down to the back with white glue or carpenter's glue. You are then ready to cover the front.

Cut your leather large enough to cover the front of the targe and overlap about an inch on the back. You will want the leather to adhere to the base, and even though there will be lots of tacks through it, it is best to glue it down. You can soak thinnish and swede leather in white glue and water, or just soak heaveier leather in water and paint on some white or carpenter's glue on the front of the targe blank. Stretch the leather over the base, tack the edges down on the back, and allow it to dry. Or you can use waterproof glue, but make sure it is evenly spread, or you will end up with a lumpy surface. Stretch the leather well, and tack the edges down as above. Make the tacks removable if you want the final decoration elsewhere!

While it's drying, get your decorating kit ready. Choose your decorative tacks and studs with two things in mind. First, you will have to have the style approved, as there are certain types of nailheads that may not be used. Check with Capt. Voorhes (Uilleam). Second, choose tacks, brads or nails with a shank shorter than the thickness of your targe (you can, of course, use a heavy wire cutter to shorten the shanks). Little bent-over nails points all over the back of your targe look (pardon the pun) really tacky, and besides that they can rip up your skin.

A word about center bosses (raised metal disks or "bowls"): Beware of using roundels from lighting fixtures and drawer pulls. Most of these designs are not acceptable for Clan use. You can try hammering your own bosses out of rounds of metal, or ask some of the other Clansmen where they got theirs.

Before tacking, draw out a design -- if you change your mind about placement of a nail, it's a lot easier to erase a drawing than to cover up an extra hole in the targe face! Most targes are divided into quarters or sixths with repeating designs. Look at pictures of old targes (not Victorian reproductions) for ideas. You can draw out the whole targe, or just make up one sector and use it for pre-marking each part of the leather in turn. Mark the targe face lightly so you can see where each nail goes. You can use different colored pens, or small and large pinholes, to show placement of different types of tacks.

Hammer the tacks in gently -- you probably don't want dents around each one! For attaching bosses, you might want to drill or poke evenly spaced holes in the rim of each boss before setting it in place on the targe face. Tack it in place lightly with a couple of nails, then drive in the holding nails.

Now! The front's done, and it looks great. Figure out which way is "up" and mark it lightly on the back side. Decide if you want one wide arm loop, or two or three narrower ones. Lay your arm down from side to side on the targe back (remember to wear whatever gloves or sleeves you will wear while carrying the targe), and measure the distance from the targe back surface, over the relevant part of your arm or hand, and down to the targe surface again. Mark where you measured from and to on the targe back. Now mark and cut your leather piece(s), adding a couple of inches for attachment. Tack your straps in place lightly and slip your arm through for a fitting. Everything OK? Make any adjustments.

Using (antiqued) screws or well-gripping short nails, attach the arm and hand loops. You may also want to add a longer strap, perhaps made out of an old belt, that you can use for slinging the targe across your back. This piece can be attached at top and bottom of targe back. and may have a buckle.

Well, there you are -- a finished masterpiece. Take good care of it, and wear it with pride!

Among the many types of

swords in use in Europe during the 16th century, one was, according to evidence, a distinctively Irish weapon. Nothing quite like it seems to have existed outside Ireland.

Among the many types of

swords in use in Europe during the 16th century, one was, according to evidence, a distinctively Irish weapon. Nothing quite like it seems to have existed outside Ireland.

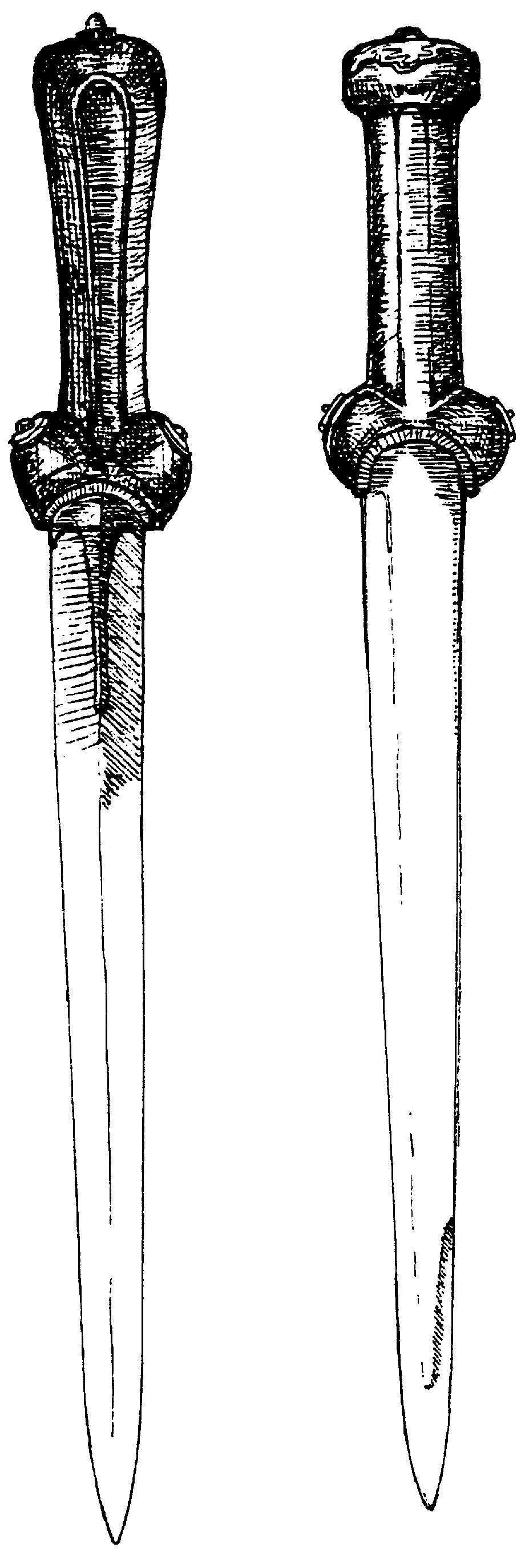

It is a sword with a long, straight, moderately broad double-edged blade, having as its most noticeable features quillions with flattened ends - fan shaped or slotted - and a pommel of an open ring within which, crossing the ring on a diameter, the end of the tang is visible. Four known specimens of this type of sword are housed in the National Museum of Ireland.

Three of them, all of the same distinctive type, are discussed at length in the book "16th Century Irish Swords," by G. A. Hayes. The first, which was illustrated by G.F. Laking in his monumental work on European armour and arms, was found at Tullylough, Co. Longford, at the end of the 19th century; for a long time it was the only sword of its kind known. The second was found during dredging operations in the river Bannat, Portglenone, Co. Antrim. The third came to light in Galway in 1948. The Tullylough and Galway swords closely resemble one another. The Portglenone sword exhibits minor differences.

Laking recognized the Tullylough sword (the only one of the three known in his time) as Irish and dated it as "probably early 17th century." He also mentioned two 16th century illustrations which show swords that are "most unusual, having flat ring-like pommels and straight quillions that widen at the ends to a form resembling the ward of a key." Curiously enough, he did not point out the remarkable similarity that exists between the Tullylough sword and these and other pictorial representations of the Irish 16th century weapons. The Tullylough sword has been dated as somewhat earlier than Laking supposed, and in view of evidence supplied by contemporary pictures, it should be looked upon as a typical Irish weapon of the 16th century. Later finds seem to bear this out.

There are five contemporary pictures, and are all well known, but they have hitherto been used more as documents in the history of Irish costume than as evidence on weapons. They are:--

A drawing made by Albrecht Durer in 1521 shows two Irish warriors and three peasants, probably in the Low Countries. Two swords are shown, both double-handers. One has an unmistakable open ring pommel which, apart from the decorative feature where the tang enters the ring, is the same as those on the three swords in the museum. The terminal of the single quillion visable is reminiscent of those on the Portglenone sword.

A woodcut in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, entitled "Irish Chieftains" shows six figures, each of whom carries a sword. All the swords have the same distinctive open ring pommel. Their general proportions are the same as those of the surviving examples save that the blades are broader. The outline of the crossguards of three of them are the same. On the other hand, the terminals of the quillions, unlike those of the Museum swords, are all either slotted like the bitt of a key or are pierced.

Three colored drawings by the Flemish artist Lucas de Heere, who worked in England from 1567 to 1577, show sword-bearing figures. They carry weapons which very closely resemble those in the Oxford print; indeed the only difference is in the scabbards, which have fringe down the sides as well as at the end. Major H.F. McClintock has suggested in @B(Old Irish Dress) that de Heere's pictures are copied from the Oxford print, and possibly from some other originals no longer in existence. He also uses them to date the Oxford print, pointing out that an inscription on one of them which reads in translation "Irishman and Irishwoman as they were attired when subjects of the late King Henry" suggests that the Oxford print is earlier than 1547.

These pictures provide ample evidence that swords with ring pommels were regarded as distinctive Irish weapons in the 16th century. Durer's picture shows that the open ring pommel was known in an Irish context as early as the first quarter of the century. It is suggested that all three weapons come from about the middle of the century, the Portglenone sword being perhaps a little earlier than the others.

The blades are almost certainly importations from the continent, like those of the contemporary Scottish claymores. The hilts, however, seem to be of native fabrication. They are part of the distinctive Gaelic order of ideas and materials that still functioned amid the turmoil of the changing world of the 16th century.

This provides a background for our three surviving specimens from Tullylough, Portglenone, and Galway, and our justification for assigning them to the 16th century.

Since the book was written a fourth sword of this group has been presented to the museum. It was found in the river Suck during cleaning operations, about five miles north of Ballinasloe, Co. Galway.

1. | A SLEIGH CO THIONAILIBH | PIKEMAN FALL IN | (ASHLAY KA TUNE A LEAVE) |

| 2. | TOGAIBH A SLEIGH | CARRY PIKES | (TOGA EEVE ASHLAY) |

| 3. | OCHIONA GRAESIBH | GENTLEMEN, FORWARD MARCH | (AWK E OWNA GRAY SEIVE) |

| 4a. | AOMAIBH A SLEIGH | PORT PIKES (TO INSIDE) | (ALMEVE ASHLAY) |

| 4b. | AOMAIBH A SLEIGH A MACH | PORT PIKES TO OUTSIDE | (ALMEVE ASHLAY A MACH) |

| 5. | DIONAIBH A SLEIGH | CHECK PIKES | (DEON EVE ASHLAY) |

| 6. | A SLEIGH DIROCHAIBH | PIKEMEN LINE IT UP! | (ASHLAY DROCK HEAVE-OR JUST: DROCK HEAVE) |

| 7. | A SLEIGH STADAIBH | PIKEMEN STOP | (ASHLAY STADEEV) |

| 8. | SILAIBH A SLEIGH | REST PIKES | (SHE LEAVE ASHLAY) |

| 9a. | FHLANNCAERANN A MACH | FLANKERS OUT | (FLANKREN A MACH) |

| 9b. | FHLANNCAERANN A STEACH | FLANKERS FORWARD | (FLANKREN A SCHTICK) |

| 9c. | FHLANNCAERANN ALMOUI | FLANKERS IN | (FLANNKREN ALM WE) |

| 10. | ANEESH! | NOW! | (ANEESH!) |

{Pikecmd.doc 11/30/89}

Chief: 3 feathers Gillan, Steven

Captains: 2 feathers Paul Mohney, Norman Montgomery, William Voorhes

Lieutenants: 1 feather Curt Cotter

Sergeants: Deer Hackel

Brevit Sgt.: Deer Hackel

Corporal: Deer Hackel

Lance Pesados:

Brevit L.P.:

Military Feathers are vertical; flat feathers denote Gentlefolk.

Copyright © June 19, 1997 Clan MacColin